Malcolm X

Title

Malcolm X

Subject

X, Malcolm, 1925-1965--Interviews

Islam

Galamison, Milton A. (Milton Arthur), 1923-1988

Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 1917-1963

King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1929-1968

Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Views on slavery

Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Views on race relations

Powell, Adam Clayton, 1908-1972

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945

Roosevelt, Eleanor, 1884-1962

Black Muslims

Civil rights movements

African American--Civil rights

Racism

Segregation

Nonviolence

Civil rights leadership

X, Malcolm, 1925-1965--Political and social views

X, Malcolm, 1925-196--Philosophy

Black nationalism--United States

African American leadership

Civil rights--leadership

African Americans--Race identity

African Americans--Religion

United States--Race relations

African Americans--Relations with Africans

Description

Malcolm X (1925-1965) was born Malcolm Little in Omaha Nebraska. After being found "mentally unfit" to fulfill his draft notice in 1943, Malcolm X was arrested in 1944 for larceny and served four months in prison. In 1945 he was convicted of grand larceny, breaking and entering, and firearms possession and was incarcerated in 1946 until 1952. While in prison Malcolm X converted to Islam and upon his release in 1952 joined the Nation of Islam in Detroit. He soon rejected the surname "Little" and became known as Malcolm X. An exceptional orator and recruiter who promoted black supremacy and was critical of nonviolence tactics in the civil rights movement, Malcolm X's popularity was second only to Elijah Muhammad's. Escalating tension with Elijah Muhammad in 1964 resulted in Malcolm X's departure from the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X then began his own organization called the Muslim Mosque Incorporated. After an international tour that included a pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm X became a Sunni Muslim and received a new Islamic name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabaz. Upon his return to the United States, although faced with significant opposition, Malcolm X continued his orating and began the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). While speaking at an OAAU rally in 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated. Three Nation of Islam members were convicted for his murder. In this interview Malcolm X discusses the connection between Islam and African American identity and describes his own conversion to Islam. He provides his opinions of the white race and the lasting effects of slavery and oppression on both the white race and African Americans. Malcolm X also questions the effectiveness of integration. He explains his belief in violent tactics in the civil rights movement against segregation and racism and criticizes nonviolent tactics. Malcolm X discusses civil rights leadership and provides his opinion of African American politicians and leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Reverend Milton Galamison, Whitney Young, Wyatt Walker, and James Baldwin. He also provides his opinion of Presidents Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, and Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt as well.

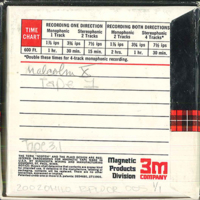

Format

audio

Identifier

2002OH110RPWCR005

Interviewer

Robert Penn Warren

Interviewee

Malcolm X

OHMS Object

OHMS Object Text

5.1 2002oh110_rpwcr005 Interview with Malcolm X, June 2, 1964 2002OH110 RPWCR 005 01:02:31 OHRPWCR Robert Penn Warren Civil Rights Oral History Project RPWCR001 Robert Penn Warren Civil Rights Oral History Project Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries (Exhibit) X, Malcolm, 1925-1965--Interviews Islam Galamison, Milton A. (Milton Arthur), 1923-1988 Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 1917-1963 King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1929-1968 Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Views on slavery Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865--Views on race relations Powell, Adam Clayton, 1908-1972 Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano), 1882-1945 Roosevelt, Eleanor, 1884-1962 Black Muslims Civil rights movements African American--Civil rights Racism Segregation Nonviolence Civil rights leadership X, Malcolm, 1925-1965--Political and social views X, Malcolm, 1925-196--Philosophy Black nationalism--United States African American leadership Civil rights--leadership African Americans--Race identity African Americans--Religion United States--Race relations African Americans--Relations with Africans Malcolm X Robert Penn Warren 2002oh110_rpwcr005_malcomx_acc001.mp3 1:|26(8)|45(8)|66(2)|84(5)|110(13)|122(6)|135(4)|153(6)|173(9)|188(7)|215(8)|251(2)|273(9)|292(7)|309(3)|331(14)|352(8)|371(5)|389(11)|409(11)|425(1)|452(3)|477(8)|495(10)|513(8)|537(13)|554(14)|569(4)|596(4)|604(4)|617(5)|641(6)|658(5)|686(7)|705(4)|727(13)|749(7)|774(6)|792(8)|809(2)|834(4)|854(8)|876(7)|891(4)|913(4)|929(6)|950(6)|975(2)|995(4)|1015(6)|1045(12)|1067(1)|1082(2)|1103(6)|1120(5)|1139(11)|1163(7)|1185(11)|1212(6)|1241(9)|1261(3)|1286(2) Spanish 1 https://oralhistory.uky.edu/spokedbaudio/2002oh110_rpwcr005_malcomx_acc001.mp3 Other audio 35 Nation of Islam and the civil rights movement Nación del Islam y el movimiento por los derechos civiles . . .Impression, correct? ¿. . . impresión, correcta? Malcolm X discusses identity and rights within the civil rights movement, specifically within the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X discute identidad y derechos dentro del movimiento de derechos civiles, específicamente dentro de la Nación del Islam. " ; Negro" ; history ; History of " ; negroes" ; ; Self improvement Historia de " ; negro" ; ; Historia de " ; negros" ; ; Auto-mejora African Americans ; Black Muslims ; Identity (Philosophical concept) ; Islam ; Leadership ; Religion Afroamericanos ; Musulmanes Negros ; Identidad (concepto filosófico) ; Islam ; Liderazgo ; Religión 17 411 The white race La raza blanca The, the white race is doomed not because. . . La, la raza blanca está condenado porque. . . Malcolm X talks about the potential doom of the white race and why this may happen. He also discusses the fight for rights. Malcolm X habla sobre el posible destino condenado de la raza blanca y por qué esto puede suceder. También discute la lucha por los derechos. American system ; Blacks ; Collective deeds ; Doomed Sistema americano ; Negros ; Hechos colectivos ; Condenados Discrimination ; Oppression ; Self-defense ; Whites Discriminación ; Opresión, Autodefensa ; Blancos 17 819 Opposition to passive resistance Oposición a la resistencia pasiva Told me to turn the other cheek. . . Me dijo que dar la otra mejilla. . . Warren and Malcolm X discuss the difference between passive resistance and self-defense. Warren y Malcolm X discuten la diferencia entre resistencia pasiva y autodefensa. " ; Turn the other cheek" ; ; Defense ; Equal rights ; Resistance " ; Dar la otra mejilla" ; ; La defensa ; La igualdad de derechos ; La igualdad de derechos relacionados ; Luchando contra ; Resistencia African Americans ; Passive resistance ; Self-defense Afroamericanos ; Resistencia pasiva ; Autodefensa 17 1083 Adam Clayton Powell Adam Clayton Powell Powell, uh, the, Adam, Adam Clayton Powell's entire political career. . . Powell, uh, el, Adam, la carrera política entera de Adam Clayton Powell. . . He discusses mature political action and Adam Clayton Powell's work as a leader and politician. Él discute la acción política madura y la obra de Adam Clayton Powell como líder y político. Adam Clayton Powell ; Fight for Afro-American causes ; mature political action Lucha por las causas afroamericanas ; Acción política madura Civil rights workers ; Independent ; Power (Social sciences) Trabajadores de los derechos civiles ; Poder (Ciencias sociales) ; Independiente 17 1270 Becoming a Muslim Convertirse en musulmán Yes, I, I, uh, strange as it may seem. . . Si, yo, yo, uh, extraño como puede parecer. . . Malcolm X talks about prison life and becoming a Muslim. Malcolm X habla sobre la vida en prisión y su convertirse en musulmán. Lack of rehabilitation ; Prison life ; Prisoners Falta de rehabilitación ; Vida carcelaria prisioneros Muslims ; Prisons Musulmanes ; Prisiones 17 1428 Reevaluating beliefs and separation from black Muslims Reevaluar las creencias y la separación de los musulmanes negros And, uh, gone through the process of re-evaluating, giving a personal re-evaluation to everything. . . Y, uh, pasado por el proceso de reevaluación, dando una reevaluación personal a todo. . . Malcolm X talks about his reevaluation of the black Muslim movement and how it compares to the fight for the rights of the American " ; negro" ; . Malcolm X habla de su reevaluación del movimiento musulmán negro y cómo se compara con la lucha por los derechos del " ; negro" ; americano. Black Muslim movement ; Reviewing religious beliefs Movimiento musulmán negro ; Revisión de las creencias religiosas Beliefs and believers Creencias y creyentes 17 1683 Dr. King and nonviolence Dr. King y la no violencia Well, see non-violence with Dr. King is only a method. . . Bueno, ver la no violencia con Dr. King es sólo un método. . . He talks about the differing methods used by Dr. King and black Muslims to fight for civil rights. Habla sobre los diferentes métodos utilizados por el Dr. King y los musulmanes negros para luchar por los derechos civiles. Different methods ; Fight for civil rights ; Similar goals Diferentes métodos ; La lucha por los derechos civiles ; Objetivos similares African Americans ; Civil rights. ; Non-violence Afroamericanos ; Derechos civiles ; La no violencia 17 1755 Answers to the problems facing Afro-Americans respuestas a los problemas que enfrentan los afroamericanos Well, uh, I might say this. . . Bueno, podría decir esto. . . Malcolm X talks about his belief that American " ; negroes" ; would have a better chance at advancement if they were to migrate to Africa for a period of time. Malcolm X habla de su creencia de que los " ; negros" ; estadounidenses tendrían una mejor oportunidad de progreso si migraran a África por un período de tiempo. " ; Back to Africa" ; ; Advancement ; Incentives ; Integration ; Issues ; Migration ; Politics ; Practical ; Self improvement ; Solutions ; Strength ; United States " ; Regreso a África" ; ; Avance ; Migración ; Auto-mejora ; Soluciones ; Fuerza ; Política ; Incentivos ; Temas ; Estados Unidos ; Integración ; Práctica Africa ; African Americans ; Civil rights ; Culture ; Economics ; Education ; Ethnicity ; Neighborhoods ; Psychology ; Race Afroamericanos ; Psicología ; Cultura ; Derechos civiles ; Educación ; La economía ; Los barrios ; La etnia ; Raza 17 2019 Reeducation for full participation Reeducación para la plena participación Yes, I do. . . Sí creo. . . He talks about the idea of " ; negroes" ; becoming full partners in all aspects of American life, not merely tokens. Habla de la idea de que los " ; negros" ; se conviertan en socios plenos en todos los aspectos de la vida estadounidense, no simplemente como testigos. " ; Negroes" ; ; Full participation ; Society " ; Negros" ; ; Plena participación ; La sociedad African Americans ; Participation Afroamericanos ; Participación 17 2213 Voter registration drives Unidades de registro de votantes Yes, we're going to give active support to voter registration drives, not only in Mississippi, but in New York City. . . Sí, vamos a dar apoyo activo para el registro de los votantes, no sólo en Mississippi, sino en la Ciudad de Nueva York. Malcolm X talks about voter registration in the South and the North and the lack of a real difference between these areas. He also states that Muslim workers should defend themselves by any means necessary. Malcolm X habla sobre el registro de votantes en el Sur y el Norte y la falta de una diferencia real entre estas áreas. También afirma que los trabajadores musulmanes deben defenderse por cualquier medio necesario. Mississippi ; New York (N.Y.) ; Non-violence La no violencia ; Nueva York (N.Y.) ; Mississippi Discrimination ; Muslims ; Voter registration Discriminación ; Registro de votantes ; Musulmanes 17 2420 Rationale for self-defense and retaliation Justificación de la autodefensa y represalias I might even answer that if I may. Incluso podría responder a eso si puedo. Malcolm X discusses war tactics and retaliation for church bombings and other violent acts. Malcolm X discute las tácticas de guerra y las represalias por los bombardeos de la iglesia y otros actos violentos. " ; Eye for an eye" ; ; Approach ; Church bombings Bombardeos de la iglesia ; " ; Ojo para un ojo" ; ; Enfoque Bombings ; Church ; Wars ; World War, 1939-1945 Los bombardeos, la iglesia, la guerra mundial, 1939-1945 ; Guerras 17 2573 What if: an ideal racial situation Qué pasa si: una situación racial ideal Let's suppose, let's suppose. . . Supongamos, supongamos que. . . He describes what it would take to have ideal race relations in the United States. Describe lo que se necesitaría para tener relaciones raciales ideales en los Estados Unidos. Colorblindness ; Ideal race relations El daltonismo ; Relaciones raciales ideales Attitude ; Islam ; Mecca (Saudi Arabia) ; Perfection ; Racism Actitud ; Islam ; La Meca (Arabia Saudita) ; Perfección ; Racismo 17 2845 Essien Udosen Essien-Udom and black nationalism Essien Udosen Essien-Udom y nacionalismo negro I was with Essien Udosen Essien-Udom in Nigeria last month. Estuve con Essien Udosen Essien-Udom el mes pasado. He discusses black Nationalism in America and the American " ; negro" ; . Habla del nacionalismo negro en América y del " ; negro" ; americano. E.U. Essien-Udom ; Nigeria ; University of Ibadan ; Value system ; White middle class values Nigeria ; Sistema de valores ; Valores de la clase media blanca ; E.U. Essien Udom ; Universidad de Ibadán Black nationalism -- United States ; Classism ; Education ; Professor Nacionalismo negro - Estados Unidos ; Clasismo ; Profesor ; Educación 17 3056 The civil rights movement and the white press El movimiento por los derechos civiles y la prensa blanca Well, uh, I can answer them like this. . . Well, uh, puedo responderles así. . . Malcolm X talks about which civil rights leaders are more apt to be followed by the white press, as well as the relationship between black leaders, the white press and the black community. Malcolm X habla sobre qué líderes de derechos civiles son más propensos a ser seguidos por la prensa blanca, así como la relación entre los líderes negros, la prensa blanca y la comunidad negra. " ; Who is known by the black community?" ; ; Black civil rights leaders ; Harlem, New York (N.Y.) ; White press ; Whitney Young ; Wyatt Tee Walker " ; Quién es conocido por la comunidad negra?" ; ; Líderes negros de los derechos civiles ; Prensa blanca ; Harlem, Nueva York (N.Y.) ; Wyatt Tee Walker ; Whitney Young African Americans ; Black Muslims ; Civil rights movement ; Newspapers ; Press ; Whites Los musulmanes negro ; El movimiento por los derechos civiles ; Blancos ; La prensa ; Periódicos 17 3196 Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt I think that he probably did more to trick " ; negroes" ; than any other man in history. Creo que él probablemente hizo para engañar a " ; negros" ; que cualquier otro hombre en la historia. He discusses Abraham Lincoln's reasons for freeing the slaves and John F. Kennedy's use of the Birmingham, Alabama situation for political gain. He also talks about the Roosevelts and their lack of fighting for the Human Rights Bill. Él discute las razones de Abraham Lincoln para liberar a los esclavos y el uso de John F. Kennedy de la situación de Birmingham, Alabama para la ganancia política. También habla de los Roosevelts y su falta de lucha por el proyecto de ley de derechos humanos. Abraham Lincoln ; Birmingham (Ala.) ; Eleanor Roosevelt ; Franklin D. Roosevelt ; freeing of the slaves and why ; John F. Kennedy ; Political gains via " ; negroes" ; ; Rioting Birmingham (Ala.) ; Liberación de los esclavos y por qué ; Ganancias políticas a través de " ; negros" ; ; Disturbios ; Abraham Lincoln ; Eleanor Roosevelt ; Franklin D. Roosevelt ; John F. Kennedy Deception ; Freedom ; Politicians ; Presidents Decepción ; Libertad ; Los políticos ; Presidentes 17 3413 James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison James Baldwin y Ralph Ellison Is a " ; negro" ; writer. . . Es un escritor " ; negro. . ." ; Malcolm X talks about James Baldwin's play " ; Blues for Mr. Charlie" ; and his disappointment with the ending. He also talks about Ralph Ellison and the invisible " ; negro." ; Malcolm X habla de la obra teatral de James Baldwin " ; Blues for Mr. Charlie" ; y su decepción con el final. También habla de Ralph Ellison y el invisible " ; negro." ; Blues for Mr. Charlie (play) ; Civil rights writers ; James Baldwin ; Nonviolence ; peaceful approach ; Ralph Ellison ; The Invisible Man (novel) Blues for Mr. Charlie (obra teatral) ; Los escritores de derechos civiles ; La no violencia ; El enfoque pacífico ; El hombre invisible (novela) ; James Baldwin ; Ralph Ellison Civil rights ; Criticism and interpretation Crítica e interpretación ; Derechos civiles 17 3590 Jawaharlal Nehru, Mao Zedong and Milton A. Galamison Jawaharlal Nehru, Mao Zedong y Milton A. Galamison About Nehru. Acerca Nehru. Malcolm X tells how he refuses to support passive leaders of other countries and black leaders within the United States. Malcolm X cuenta cómo se niega a apoyar a los líderes pasivos de otros países y líderes negros dentro de los Estados Unidos. Dislike ; Jawaharlal Nehru ; Mao Zedong ; Milton Galamison Disgusto ; Milton Galamison ; Mao Zedong ; Jawaharlal Nehru Leaders ; Pacifism ; Politicians El pacifismo ; Líderes ; Políticos 17 Malcolm X (1925-1965) was born Malcolm Little in Omaha Nebraska. After being found " ; mentally unfit" ; to fulfill his draft notice in 1943, Malcolm X was arrested in 1944 for larceny and served four months in prison. In 1945 he was convicted of grand larceny, breaking and entering, and firearms possession and was incarcerated in 1946 until 1952. While in prison Malcolm X converted to Islam and upon his release in 1952 joined the Nation of Islam in Detroit. He soon rejected the surname " ; Little" ; and became known as Malcolm X. An exceptional orator and recruiter who promoted black supremacy and was critical of nonviolence tactics in the civil rights movement, Malcolm X's popularity was second only to Elijah Muhammad's. Escalating tension with Elijah Muhammad in 1964 resulted in Malcolm X's departure from the Nation of Islam. Malcolm X then began his own organization called the Muslim Mosque Incorporated. After an international tour that included a pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm X became a Sunni Muslim and received a new Islamic name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabaz. Upon his return to the United States, although faced with significant opposition, Malcolm X continued his orating and began the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU). While speaking at an OAAU rally in 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated. Three Nation of Islam members were convicted for his murder. In this interview Malcolm X discusses the connection between Islam and African American identity and describes his own conversion to Islam. He provides his opinions of the white race and the lasting effects of slavery and oppression on both the white race and African Americans. Malcolm X also questions the effectiveness of integration. He explains his belief in violent tactics in the civil rights movement against segregation and racism and criticizes nonviolent tactics. Malcolm X discusses civil rights leadership and provides his opinion of African American politicians and leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Reverend Milton Galamison, Whitney Young, Wyatt Walker, and James Baldwin. He also provides his opinion of Presidents Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, and Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt as well. WARREN: This is the first tape of a conversation with Minister Malcolm X, June second. [Pause in recording.] WARREN: From what I have read, which includes books I could find and a good many articles on the Black Muslim position and on yourself, it seems that the identity of the negro is the key fact that you deal with, is that true? Is that impression correct? MALCOLM X: Yes. Yes, and, and not, not so much in the sense of the Black Muslim religion. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: Both of them have to be separated. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: The black people in this country are taught that their religion and the best religion is the religion of Islam, and when one accepts the religion of Islam, he' ; s known as a Muslim. He becomes a Muslim. That means he believes that there' ; s no God but Allah and that Mohammed is the apostle of Allah. Now besides teaching him that Islam is the best religion, since the main problem that American, the Afro- Americans have is a lack of cultural identity. It is necessary to teach him that he had some type of identity, culture, civilization before he was brought here. Well, now, teaching him about his historic or cultural past is, is not his religion. This is not, it' ; s not religious. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: The two have to be separated. WARREN: Yes. Or what about the matter of, of personal identity as related to cultural and blood identity? MALCOLM X: I don' ; t quite understand what you mean. WARREN: I mean, I' ; m trying to get at this. That is, a man may know that he belongs to, say, a group--this group or that group--but he feels himself lost within that group, trapped within his own deficiencies and without personal purpose. Lacking personal identity, you see. MALCOLM X: Yes. Well, the, the religion of Islam actually restores one' ; s human feelings, human rights, human incentives, human, his talent. The religion of Islam brings out of the individual all of his dormant potential. It, it gives him the incentive to develop his dormant potential so that when he becomes a part of the brotherhood of Islam, and is identified collectively in the brotherhood of Islam with the brothers in Islam, at the same time this also gives him the, it has the psychological effect of giving him the incentive as an individual to develop all of his dormant potential to its fullest extent. WARREN: A personal regeneration then-- MALCOLM X:--yes-- WARREN:--is associated automatically with this? MALCOLM X: Oh, yes. Yes. WARREN: Sometimes in talking with negroes in other organizations and other persuasions, I' ; ve found out that there' ; s a deep suspicion of any approach which involves the old phrase " ; self improvement," ; you see-- MALCOLM X:--yes-- WARREN:--and to state the matter on objective, impersonal matters such as civil rights, integration, or job programs, and not on the question of self improvement, or you might say the individual responsibility. MALCOLM X: That-- WARREN:--but you, you take a different line. MALCOLM X: Definitely. Most of the, or I should say many of the negro leaders actually suffer themselves from an inferiority complex even though they say they don' ; t. And because of this they have subconscious defensive mechanisms which they' ; ve erected without even realizing it. So that when you mentioned something about self improvement, the implication is that the negro is something distinct or different, and, therefore, needs to learn how to improve himself. Negro leaders resent this being said, not because they don' ; t know that it' ; s true, but they' ; re thinking, they' ; re looking at it personally. They think that the implication is directed even at them, and that they, and they duck this responsibility. Whereas the only real solution to the race problem in this country is a solution that involves individual self improvement and collective self improvement in, whereas our own, wherein our own people are concerned. WARREN: Could you tell me or would you be willing to, or do you think it' ; s relevant, some detail of your own conversion to Islam? MALCOLM X: Well, I was in prison. WARREN: I know that fact, yes. MALCOLM X: And, and-- WARREN:--I' ; m asking about the interior feeling of the-- MALCOLM X: --yes-- WARREN:--process. MALCOLM X: Yes. Well, I was in prison and I was an atheist. I didn' ; t believe in anything. And I had begun to read books and things and, in fact, one of the persons who started me thinking seriously was an atheist that I, another negro inmate whom I' ; d heard in a discussion with white inmates and who was able to hold his own at all levels. And he impressed me with his knowledge, and I began to listen very carefully to some of the things he said. And it was he who switched my reading habits in a direction away from fiction to non-fiction, so that by the time one of my brothers told me about Islam, although I, although I was an atheist, I was open-minded, and I began to read in that direction, in the direction of Islam, and everything that I read about it appealed to me. And one of the main things that I read about it that appealed to me was in Islam a man is re--is regarded as a human being. He' ; s not measured by the color of his skin. At this point I hadn' ; t yet gotten deep into the historic condition that negroes in this country are confronted with, but at that point in my prison studies I, I read, I studied Islam as a religion more so than as I later come to know it in its connection with the plight or problem of Negroes in this country. WARREN: This is getting ahead a little bit but it seems to apply here. If Islam teaches the human worth of, of all men without reference to color, how does that fact relate to the message of, of black superiority and the doom of the white race? MALCOLM X: Well, the, the white race is doomed not because it' ; s white but because of its deeds, and the people listening very closely to what the Muslims have always declared -- WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: They' ; ll find that in every declaration there' ; s the fact that, the same as, as Moses told Pharaoh, " ; You' ; re doomed if you don' ; t do so and so," ; or as Daniel told, I think it was Balthazar or Nebuchadnezzar, " ; You are doomed if you don' ; t do so and so." ; Now, always that " ; if" ; was there, which meant that the one who was doomed could avoid the doom if he would change his way of behaving. Well, it' ; s the same here in America. When the Muslims deliver the indictment of the American system, it is not the white man per se that is being doomed. WARREN: It' ; s not blood itself that' ; s being--there' ; s no blood damnation then? MALCOLM X: No. But, see, the, it' ; s almost impossible to separate the actions, or it' ; s also, it' ; s almost impossible to separate the oppression and exploitation, criminal oppression and criminal exploitation of the American negro from the color of the skin of the person who is the oppressor or the exploiter. So, he thinks he' ; s being condemned because of his color but actually he' ; s being condemned because of his deeds, his conscious behavior. WARREN: Let' ; s take the question like this: can a person, an American of white blood, be guiltless? MALCOLM X: Guiltless? WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: Well, the, the, you have, you can only answer it this way: by turning it around. Can the negro--who is the victim of the system--escape the collective stigma that is placed upon all negroes in this country? And the answer is " ; No." ; Because Ralph Bunche, who is an internationally recognized and respected diplomat, can' ; t stay in a hotel in Georgia, which means that no matter what the accomplishment, the intellectual, the academic, or professional level of a negro is, collectively he stands condemned. Well, the white race in America is the same way. As individuals it is impossible for them to escape the collective crime committed against the negroes in this country, collectively. It' ; s-- WARREN: --let' ; s take an extreme case like this, just the most extreme example I can think of. Let us say a white child of three or four, something like that, who is outside of conscious decisions or, or valuations is facing accidental death, you see. Is the reaction to that child the same as the reaction to a, a negro child facing the same situation? MALCOLM X: Well, just take the negro child. Take the white child. The white child, although it has not committed any of the per--as a person has not committed any of the deeds that has produced the plight that the negro finds himself in, is he guiltless? The only way you can determine that is, take the negro child who' ; s only four-years-old. Can he escape, though he' ; s only four years old, can he escape the stigma of discrimination and segregation? He' ; s only four-years-old. WARREN: Let' ; s put him in front of the oncoming truck and put a white man on the pavement who must risk his life to leap for the child. Let' ; s reverse it. MALCOLM X: I, I don' ; t see where that-- WARREN:--some white man would leap ; some wouldn' ; t leap. MALCOLM X: It, it would not, it still wouldn' ; t alter the fact that after that white man saved that little black child, he couldn' ; t take that little black child in many restaurants, hotels, in places right along with him. WARREN: Um-hm. MALCOLM X: Even after the child, the life of the black child was saved, but that same white man will have to toss him right back into the discriminate, into discrimination, segregation, and these other things. WARREN: Well, suppose, let' ; s take a case, suppose that white man is prepared to go to jail to break segregation? MALCOLM X: His going to jail to break segregation still has, and if he broke segregation-- WARREN:--just keep it on the individual, this one white man. MALCOLM X: You can' ; t solve it individually. WARREN: But what you' ; re having toward the one white man who goes to jail, say, not once but over and over again, say, in-- MALCOLM X:--this has been going on for the past ten years. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: White individuals that have been going to jail. Segregation still exists ; discrimination still exists. WARREN: Yes, that' ; s true. But what is the attitude toward the white man who does this, who goes to jail? MALCOLM X: My personal attitude. WARREN: That' ; s what I mean. MALCOLM X: Is that he has done nothing to solve the problem. WARREN: What' ; s your attitude toward his moral nature? MALCOLM X: Not even interested in his moral nature. Until the problem is solved, we don' ; t, we' ; re not interested in anybody' ; s moral nature. WARREN: As all-- MALCOLM X:--but what I' ; m boiling down to say is that the, a few isolated white people whose individual acts are designed to eliminate this, that or, or the next thing but, yet, it is never eliminated is in no way impressive to me. WARREN: That is, you couldn' ; t call that man a friend? MALCOLM X: If his own rights were being trampled upon as the rights of negroes are being trampled upon, he would use a different course of action to protect his rights. WARREN: What course of action? MALCOLM X: (laughs) I have never seen white people who would sit, who would, who would approach a solution to their own problems nonviolently or passively. It' ; s only when they are so-called " ; fighting for the rights of negroes" ; that they nonviolently, passively, and lovingly, you know, approach the situation. But when the whites themselves are attacked, they believe in defending themselves and things of that sort. But those type of whites who are always going to jail with negroes are the ones who tell negroes to be loving and be kind and be patient and be nonviolent and turn the other cheek. WARREN: But-- MALCOLM X:--so if I did see a white man who was willing to go to jail or throw himself in front of a car in behalf of the so-called " ; negro cause," ; the test that I' ; d put to him, I' ; d ask him, " ; Do you think negro, when negroes are being attacked they should defend themselves even at the risk of having to kill the one who' ; s attacking them?" ; If that white man told me, " ; Yes," ; I' ; d shake his hand. I, I' ; d trust in him. But I don' ; t trust any white man who teaches negroes to turn the other cheek or to be nonviolent, which means to be defenseless in the face of a very brutal, criminal enemy. No. That' ; s my yardstick for measuring whites. WARREN: Now, the question, what is defenseless at this point? MALCOLM X: Anytime you tell a man to turn the other cheek or to be nonviolent in the face of a violent enemy, you' ; re making that man defenseless. You' ; re robbing him of his God-given right to defend himself. WARREN: Let' ; s take a concrete case again on the question of defenselessness just to be sure I understand you. If, say, in the case of Dr. Aaron Henry in Mississippi, Clarksdale, Mississippi, his house has been bombed and has been shot through and that sort of thing. Well, he is armed. I' ; ve been in his house. I know he' ; s armed. He, his guards are sitting there with arms, with the arms that they' ; re, in their hands at night. And everybody knows this. Now, I can' ; t see how anyone would ask him not to defend himself, you see? If defense is literally defense, as it' ; s taken in ordinary legal times, or a mounted aggression for purposes of defense is another thing in society, you see what I' ; m getting at? A man sitting in his own house -- MALCOLM X: I think that a negro-- WARREN:-- (??) is one thing. A man who goes out and performs an act of violence as is some sort of a (??) long-range defense. MALCOLM X: I think that the negro should reserve the right to execute- -[knocks on table]--any measure necessary to defend himself. Any way, any form necessary to defend himself ; he should reserve the right to do that just the same as others have the right to do it. WARREN: Well, political assassination, for instance? MALCOLM X: I don' ; t know anything about that. I, I wouldn' ; t even answer a question like that. WARREN: Um-hm. MALCOLM X: But I say that the negro, when he is, when, when they cease to look at him as a negro and realize that he' ; s a human being, then they will realize that he is just as capable and has the right to do anything that any other human being on this earth has a right to do to defend himself. WARREN: Well, there are millions of, of white people who would say right away that the negro should have, any negro should have the same legal rights to defense that a white man has. MALCOLM X: And I think you' ; ll find also that if the negro ever realizes that he should begin to fight for real for his freedom, there are many whites who will fight on his side with him. It' ; s not a case where people think he' ; ll be the underdog or be outnumbered. But there are many white people in this country who realize that the system itself-- as it is constructed--is not so constructed that it can produce freedom and equality for the negro, and the system has to be changed. It is the system itself that, that is incapable of producing freedom for the twenty-two million Afro-Americans. Just like a chicken can' ; t lay a duck egg, a chicken can' ; t lay a duck egg, because the system of the chicken isn' ; t constructed in the way to produce a duck egg. And just as that chicken system can' ; t produce, is not capable to, of producing a duck egg, the political and economic system of this country is absolutely incapable of producing freedom and justice and equality and human dignity for the twenty-two million Afro-Americans. WARREN: You don' ; t see in the American system the possibility of self- regeneration then, -- MALCOLM X: No, nothing ; there' ; s nothing in-- WARREN:--of change? MALCOLM X: No. There, the American system itself is incapable. It' ; s, it is as incapable of producing freedom for the Afro-American as a, as the system of a chicken is of producing a duck egg. WARREN: You don' ; t see any possibility of gains or, or better solutions through political-- MALCOLM X:--no-- WARREN:--negro political action or, or economic action? MALCOLM X: Well, any time the negro becomes involved in mature political action, then the resistance of the politicians who, who benefit from the exploited political system as it now stands, will come, will, will be forced to put, exercise more violent action to deprive the negro of his mature political action. WARREN: Do you think that Adam Clayton Powell' ; s political career has been one of mature political action? He thinks highly of you. He speaks high--he speaks to me highly of you. MALCOLM X: Adam Clayton Powell, the, Adam, Adam Clayton Powell' ; s entire political career has to be looked at in the entire context of the American history and the history of, and the position of the Afro- American or negro in American history, and then when they, and, and when you take all of these factors in con-, factors combined you can see where Adam Clayton Powell is a remarkable man and has done a-- WARREN: --yes-- MALCOLM X:--and has done a remarkable job in fighting for rights of black people in this country. On the other hand, he probably hasn' ; t done as much as he could or as much as he should because he is the most independent negro politician in this country. There' ; s no politician in this country of na-, national stature who is more independent of the political machine as Adam Clayton Powell is. WARREN: Well, Dawson' ; s a pure victim of it, of course, in Chicago, Congressman Dawson. MALCOLM X: Yes. I don' ; t know too much about Dawson, but from what I' ; ve heard, he' ; s more, he has no independence of action when it comes to the political machine there-- WARREN:--that' ; s my understanding-- MALCOLM X:--in Chicago. WARREN: But is that li-, is his, is Adam Clayton Powell' ; s line a line of what you' ; d call " ; mature political action," ; or has that been frustrated and-- MALCOLM X:--in my opinion, mature political action is the type of action that enables the, that involves a program of re-education and information that will enable the black people in the black community to see the fruits that they should be receiving from the politicians who are over them and, thereby, they are then able to determine whether or not the politician is really fulfilling his function. And, and if he is not fulfilling his function, they then can set up the machinery to remove him from that position by whatever means necessary. To me, political action involves making the politician who represents us know that he either produces or he is out, and he' ; s out one way or another. WARREN: There' ; s only one way to put a politician out ordinarily, it' ; s to vote him out. MALCOLM X: Well, I think that the black people in this country have the reached the point where they should reserve the right to do whatever is necessary to see that they exercise complete control over the politicians in the politician, in the politics of their own community by whatever means necessary. WARREN: Let' ; s go back to the matter of your conversion, or some of the details of that. Was it fast or slow, a simple a matter as that? Was it a-- MALCOLM X:--it was fast-- WARREN:--flash, a flash-- MALCOLM:--yes-- WARREN:--of intuition? MALCOLM X: No, it was fast. I, I, strange as it may seem, I turned, I think I took an about-turn overnight. WARREN: Really overnight, just like that? MALCOLM X: Yes. And while I was in prison and wasn' ; t a Muslim, I was indulging in all types of vice, right within the prison. And I never was ostracized as much by the penal authorities while I was participating in all of the evils of the prison, as they tried to ostracize me after I became a Muslim. WARREN: Why was that? MALCOLM X: Well, the prison systems in this country actually are exploitive and they are not in any way rehabilitative. They' ; re not designed to rehabilitate the--the inmate, though the, the public propaganda is that this is their function. But they, the, most people who work in prison earn money through contraband. They--they earn their, they earn extra money by selling contraband, dope, and things of that sort to the inmates, and so that really it' ; s an exploiter. WARREN: This was a matter of defending their commercial interests-- MALCOLM X:--right-- WARREN:--their economic interests and not a matter of fear of the Muslim movement, is that it? MALCOLM X: Both. WARREN: Oh, it' ; s both. MALCOLM X: It' ; s, it' ; s both. They have a fear of the, the Muslim movement and the Muslim religion because it has a tendency to make the people who accept it stick together. And I had one warden tell me since I' ; ve been out, and I visited an inmate in prison right here in New York, Warden Fay up at Green Haven-- WARREN:--Fain? MALCOLM X: Fay. Fay, F-A-Y. In 1959 or ' ; 58, along in there, I visited an inmate in prison and he told me that he didn' ; t want anybody in there trying to spread this religion. And I asked him at that time if, if it didn' ; t make a better inmate out of the negroes who accepted it and he said, " ; Yes." ; So I asked him then what was it about it that he considered to be so danger, and he, dangerous, and he pointed out that it was the cohesiveness that it produced among the inmates. They stuck together. What you did to one, you did to all. So they couldn' ; t have that type of religion being taught in the prison. WARREN: Just a matter of maintaining their own control then? MALCOLM X: Yes. WARREN: Has there been any change in your religious beliefs since your break last (??) last fall? MALCOLM X: Well, I have gone through the process of re-evaluating, giving a personal re-evaluation to everything that I ever believed and that I did believe while I was a, a member and a minister-- WARREN:--yes-- MALCOLM X: --in the black, in what we call the Black Muslim movement. WARREN: May I ask how you' ; ve come out of that evaluation? MALCOLM X: Well, first I might say that when a person, when a man separates from his wife, at the out start it' ; s a physical separation but it' ; s not a psychological separation. He still thinks of her in, in probably warm terms. And, but after the physical separation has taken, existed for a period of time, it becomes a psychological separation as well as physical. And he can then look at her more objectively. My split or separation from the Black Muslim movement at first was only a physical separation, but my heart was still there and it was impossible for me to, for me to look at it objectively. After I made my tour in the Middle, into the Middle-East and Africa and visited Mecca and other places, I think that the separation became psychological as well as physical, so that I could look at it more objectively and--and separate that which was good from that which was bad. WARREN: Well, what did you find, if I may ask, good and what' ; s bad in this re-evaluation? MALCOLM X: Well, I think now I, it' ; s, it' ; s possible for me to approach the whole problem with a broader scope, much broader scope. When you look at something through an, an organizational eye, whether it' ; s a, a religious organization, political organization, or a civic organization, if you look at it only through the eye of that organization, you see what the organization wants you to see. But you lose your ability to be objective. But when you aren' ; t affiliated with anything, and then you look at something, you look at it with your eye to your, to the best of your ability-- WARREN:--well, for example-- MALCOLM X:--and see it as it is. WARREN: For example, what specific thing do you now see as is and not through organizational eyes? MALCOLM X: Well, I can, I look at the problem of the twenty-two million Afro-Americans as being a problem that' ; s so broad in scope that it' ; s almost impossible for any organization to see it in its entirety. And because the average negro organization, especially, can' ; t see the problem in its entirety. They can' ; t even see that the problem is so big that their own organization as such, by itself, can never come to a, can never come up with a solution. The problem is so broad that it' ; s going to take the inner working of all organizations. It' ; s going to take a, a united front of all organizations, looking at it with more objectivity, to come up with a solution that will, that will stand against the whites. WARREN: Would you work, would you work then with the SCLC, Dr. King' ; s organization? MALCOLM X: Well, even as a Muslim minister in the Muslim movement, I have always said that I would work with any organization. But I, I can say it even more ho-, with more honesty now. Then when I said it I would make the, the reservation that I would work with any organization as long as it didn' ; t make us compromise our religious principles. Now I think that the problem of the American negro goes beyond the principle of any organization whether it' ; s a religious, political, or otherwise. The problem of the negro is so criminal that many individuals and organizations are going to have to sacrifice what they call their organizational principles if someone comes up with a solution that will really solve the problem. If it' ; s a solution they, they want, they should go, they should, they should accept the solution. But if it' ; s a solution they want as long as it doesn' ; t interfere with their organization, then it means they' ; re more concerned with their organization than they are with getting a solution to the problem. WARREN: Because I' ; m trying to see how it would be possible to work with the, Dr. King' ; s philosophy of nonviolence, you see. MALCOLM X: Well, see, now, nonviolence with Dr. King is only a method. That' ; s not his objective. WARREN: Yes. No, it' ; s not his objective but -- MALCOLM X: Well, his objective, I think, is to gain, gain respect for negroes as human beings. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: And nonviolence is his, is his method. Well, my objective is the same as King' ; s. Now, we may disagree on methods, but we don' ; t have to argue all day on methods. Forget the methods or the differences in methods. As long as we agree that the thing that the Afro-American wants and needs is recog-, is recognition and respect as a human being. WARREN: This is the end of tape 1 of a conversation with Minister Malcolm X. Proceed. [Tape 1 ends ; tape 2 begins.] WARREN: This is tape 2 of a conversation with Minister Malcolm X. Proceed. [Interruption in taping] Would you change, in the evaluation of the Black Muslim movement in America, have you changed your view about separatism, political separatism, the actual formation of an independent state of some kind? MALCOLM X: Well, I might say this, that the problem of the, the solution for the Afro-American is two-fold--long-range and short-range. I believe that a psychological, cultural, and philosophical migration back to Africa will solve our problem. Not a physical migration, but a cultural, psychological, philosophical migration back to Africa, which means the restoring our common bond will give us the spiritual strength and the incentive to strengthen our political and social and economic position right here in America, and to fight for the things that are ours by right here on this continent. And at the same time, this will also tend to give incentive to many of our people then to want to also visit and even migrate physically back to Africa. And those who stay here can help those who go back, and those who go back can help those who stay here in the same way that when Jews go to Israel, the Jews in America help those in Israel and the Jews in Israel help those in America. WARREN: Is that, that' ; s the long-range, the second thing is your long- range solution, is that it? MALCOLM X: Sir? WARREN: The second thing is a long-range solution? There are two, two accepted solution. One' ; s a short-range. MALCOLM X: Yes. WARREN: One' ; s the long-range? MALCOLM X: The short-range, the short-range involves the long-range. Immediate steps have to be taken to reeducate our people-- WARREN:--yes-- MALCOLM X:--into the, a more real view of political, economic, and social conditions in this country, and our ability in, in a self- improvement program to gain control politically over every community in which we predominate, and also over the economy of that same community as here in Harlem. Instead of all the stores in Harlem being owned by white people, they should be owned and operated by black people. The same as in a German neighborhood, the stores are run by Germans, and in a Chinese neighborhood they' ; re run by Chinese. In the negro neighborhood the businesses should be owned and operated by negroes and, thereby, they would be employing, and, and they would be creating employment for negroes. WARREN: Right. You are thinking then of, of these, you might say, localities as being then operated by negroes, not in terms of a sep-, a political state, a separate nation? MALCOLM X: No. The separating of, of a section of America for Afro- Americans is similar to expecting a heaven in the sky somewhere after you die. WARREN: It' ; s not practical then? MALCOLM X: To say it is not practical, one has to also admit that integration is not practical. WARREN: I don' ; t quite follow that. MALCOLM X: In--in stating that the idea of a separate state is not practical, I' ; m also stating that the idea of integration, forced integration, as they' ; ve been making an effort to do in this country for-- WARREN:--yes-- MALCOLM X:--the past ten years, is just al-, is also just as impractical. WARREN: That both these poles, these two opposites-- MALCOLM X: --both are impractical-- WARREN:--simply aren' ; t practical? MALCOLM X: Yes. Both of them are impractical. WARREN: You can envisage negro sections or negro communities which are self, self-determining-- MALCOLM X:--yes, I do-- WARREN:--as a better solution? MALCOLM X: Until a reeducation program is, is devised to bring our people to the intellectual, economic, political, and social level wherein we can control, own, operate our own communities economically, politically, socially, and otherwise, why any solution that doesn' ; t involve that is not even a solution. Because if I can' ; t run my neighborhood you won' ; t want me in your neighborhood. WARREN: You are saying, in other words, you see neighborhoods and communities that are, that are all Afro-American and self-determining but these are parts of a larger political unity as-- MALCOLM X:--yes-- WARREN:--the United States? MALCOLM X: Because once the black man becomes the political master of his own community, it means that the politicians of that community will also be black, which also means that he then will be sending black representation or representatives not only to represent him at the local level and at the state level, but, but even at the federal level. See, all throughout the South in, in areas were the black man predominates, he would have black representatives in Washington, DC. Well, my contention is that the political system of this country is so designed criminally to prevent this, that if the black man even started in that direction, which is a mature step and it' ; s the only way to really solve this problem and to prove that he is the intellectual equal of others, why, the--the racists and the segregationists would fight that harder than they' ; re fighting the present efforts to integrate. WARREN: They' ; ll fight it, yes. Let me ask you two questions around this. One, there are negroes now holding a prominent place at the federal level. MALCOLM X: They' ; ve been put there -- WARREN: Like Dr. Weaver and-- MALCOLM X:--I don' ; t mean-- WARREN:--Mr. Rowan and people like that. MALCOLM X: I don' ; t mean neg-, those kind of negroes who are placed in big jobs as window dressing. I, I refer to a negro politician as a negro who is selected by negroes, who, and who is backed by negroes. Most of those negroes have been given those jobs by the white political machine, and they serve no other function other than to, as window dressing. WARREN: Ralph Bunche, too? MALCOLM X: Any negro who occupies a position that was given to him by the white man, if you analyze his function, his function never enables him to really take a firm, uncompromising, militant stand on problems that confront our people. He opens up his mouth only to the degree that the political atmosphere at the time will allow him to do so without rocking the boat too much. WARREN: Is your organization supporting the voter registration drive in Mississippi this summer? MALCOLM X: Yes, we' ; re going to work. WARREN: Actively? MALCOLM X: Yes, we' ; re going to give active support to voter registration drives, not only in Mississippi, but in New York City. I just can' ; t see where Mississippi is that much different from New York City. Maybe in method or-- WARREN:--I don' ; t either. MALCOLM X: No, I don' ; t see, I never will let anyone make, maneuver me into making a distinction between the Mississippi form of discrimination and the New York City form of discrimination. It' ; s, it' ; s both discrimination ; it' ; s all discrimination. WARREN: Are you actually putting workers in Mississippi this summer? MALCOLM X: We will. They won' ; t be nonviolent workers. WARREN: Nonviolent in which sense? Upon attack or-- MALCOLM X:--we will never send a negro anywhere and tell him to be nonviolent. WARREN: Um-hm. If he is shot at, shoot back? MALCOLM X: If he' ; s shot at, shoot back. WARREN: What about the matter of nonselective reprisals? Say, if a negro is shot in Mississippi and like Medgar Evers, for instance, then shooting a white man or trying to shoot a responsible white man? MALCOLM X: Well, I' ; ll tell you. If I go home and someone, and my child has blood running down her leg and someone tells me that a snake bit her, I' ; m going out and kill the snake. And when I find the snake, I' ; m not going to look and see if he has blood on his jaws. WARREN: You mean you' ; ll kill any snake you find? MALCOLM X: I grew up in the country on a farm-- WARREN:--so did I. MALCOLM X: And it was whenever someone said even that a snake was eating the chickens or bothering the chickens, we' ; d kill snakes. We never knew whether that was the snake that did it. WARREN: To, to read your parallel then, you would advocate nonselective reprisal: kill any white person around. MALCOLM X: I' ; m not saying that ; I' ; m just telling you about snakes. WARREN: Yeah, okay. (laughs) All right. We' ; ll settle for that. MALCOLM X: Well, I mean what I say. WARREN: Um-hm. I know what you say. I know how the parables work. Let us suppose that we had--just suppose. MALCOLM X: Then, perhaps, you know the other, when the snakes out in that field begin to realize that if one of their members get out of line, it' ; s going to be detrimental to all of them, they' ; ll keep that, perhaps they' ; ll then take the necessary steps to keep their fellow snakes away from my chickens or away from my children if the responsibility is placed upon them. WARREN: Suppose we had--this is, maybe it' ; s a big supposition--but suppose we had an adequate civil rights legislation and fair employment-- MALCOLM X: --I might even answer that, if I may. WARREN: Yes, please, go ahead. MALCOLM X: I believe when a negro church is bombed, that a white church should be bombed. WARREN: Reprisal. MALCOLM X: I believe it, yes. Can I--and I can give you the best example. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States struck back. She didn' ; t go and bomb--she bombed any part of Japan. She dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. Those people in Hiroshima probably hadn' ; t even, some of them ; most of them hadn' ; t even killed anybody. WARREN: Sure. MALCOLM X: But still she dropped that bomb. I think it killed eighty- some thousand people. Well, this is internationally recognized as a way, as--as justifiable during war. Any time a negro community- -(knocks on table)--lives under fear that its churches are going to be bombed, then they have to realize they' ; re living in a war zone. And once they recognize it as such, they can adopt the same measures against the community that harbors the criminals who are responsible for this activity. WARREN: Now we have it. Now we have it. It' ; s a question of, of a negro, say, in Birmingham, being outside of the community, being no part of the community, so he takes the same kind of reprisal he would take in wartime? MALCOLM X: He should realize that he is living in a war zone, and he is at war with an enemy that is as vicious and criminal and inhuman as any war-making country has ever been. WARREN: Um-hm. MALCOLM X: And once he realizes that, then he can defend himself. WARREN: By the way, tell me--if you will--what was the exact content of the--[telephone rings]--want me to cut this off? MALCOLM X: Yes. [Pause in recording.] WARREN: Now cutting back to what I was about to say a moment ago. Suppose you had an adequate civil rights legislation enforced-- suppose--suppose you had a fair employment practice code enforced. Suppose you had a thing, by-and-large civil rights organizations looked to you as their--[interruption in taping]--suppose we had had the objectives demanded by most civil rights organizations now actually existing--(Malcolm X laughs)--then what? MALCOLM X: Suppose. WARREN: Just suppose. (Malcolm X laughs) Let' ; s suppose ; let' ; s suppose. MALCOLM X: You' ; d have civil war. You' ; d have a race war in this country. In order, in order to enforce, see, you can' ; t force people to act right toward each other. You can' ; t force, you cannot legislate heart, conditions and attitudes. And when you have to pass a law to make a man let me have a house, or you have to pass a law to make a man let me go to school, or you have to pass a law to make a man let me walk down the street, you have to enforce that law and you' ; d have to be living actually in a police state. It would take a police state in this country. I mean a real police state right now just to get a token recognition of a law. It take, it took, I think, 15,000 troops and 6 million dollars to put one negro in the University of Mississippi. That' ; s a police action, police state action. WARREN: That' ; s a police action. MALCOLM X: So, actually, all of the civil rights problems during the past ten years have created a situation where America right now is moving toward a police state. You can' ; t have anything otherwise. So that' ; s your supposition. WARREN: All right. Then you see no possibility of a self-regeneration for our society then? MALCOLM X: When I was in Mecca-- WARREN:--yes-- MALCOLM X:--I noticed that their, they had no color problem. That they had people there whose eyes were blue and people there whose eyes were black, people whose skin was white, people whose skin was black, people whose hair was blond, people whose hair was black, from the whitest white person to the blackest black person. WARREN: I read your letters. MALCOLM X: There was no racism ; there was no problem. But the religious philosophy that they had adopted, in my opinion, was the only thing and is the only thing that can remove the white from the mind of the white man and the negro from the mind of the negro. I have seen what Islam has done with our people, our people who had this feeling of negro and- -and it had a psychological effect of putting them in a, in a mental prison. When they accepted Islam, it removed that. Well, white people whom I have met, who have accepted Islam, they don' ; t regard themselves as white but as human beings. And by looking upon themselves as human beings, their whiteness to them isn' ; t the yardstick of perfection or honor or anything else. And, therefore, this creates within them an attitude that is different from the attitude of the white that you meet here in America, because then, and it, and it was in Mecca that I realized that white is actually an attitude more so than it' ; s a color. And I, and I can prove it because among negroes we have negroes who are as white as some white people. Still there' ; s a difference. WARREN: I was about to ask you about, what is a negro? MALCOLM X: Yeah, it' ; s an attitude. I' ; ll tell you what it is. And white is an attitude. And it is the attitude of the American white man that is making him stand condemned today before the eyes of the entire dark world and even before the eyes of the Europeans. It is his attitude, his haughty, holier-than-thou attitude. He has the audacity to call himself even the " ; Leader of the Free World" ; while he has a country that can' ; t even give the basic human rights to over twenty-two million of its citizens. This is aud-, this is, this takes audacity ; this takes nerve. So it is this attitude today that' ; s causing the Americans to be condemned. WARREN: What view do you take of the western European white as opposed to the American white? MALCOLM X: Well, there' ; s a great deal of difference in the, a great deal of difference in the, when you say west European, even, even, there' ; s a difference between the western European and the eastern European. WARREN: That' ; s what I' ; m talking about. MALCOLM X: Oh, yes. But there' ; s a great deal of dif-, there' ; s a difference in them. Many of them who belong to these countries that were former colonial powers have racist attitudes, but their racist attitude is never displayed to the degree that the America' ; s attitude of racism is displayed. Never. WARREN: You know the book by Essien Udom on, called Black Nationalism? I know you must. MALCOLM X: I was with Essien Udom in-- WARREN:--you were? MALCOLM X:--in Nigeria last month. WARREN: I wish you' ; d tell me about him. Who is he? MALCOLM X: Well, he' ; s a Nigerian. At present he' ; s a professor at Ibadan University. WARREN: Ah! I didn' ; t know where he was. Now I knew he was a scholar. MALCOLM X: Yes. WARREN: Do you agree with his analysis that the, the Black Muslim religion, Islam in America, has served as a concealed device to gratify the, the American negro' ; s aspirations to white middle-class values? MALCOLM X: No, I don' ; t think-- WARREN:--he takes that view, you know. MALCOLM X: Yes, but I don' ; t think that the objective of the American negro is white middle-class values because what are white middle-class values? And what makes the whites who have these middle-class values have those values? Where did they get it? They didn' ; t have these same values, you know, four hundred years, five hundred years ago. Where did they get their value system that they now have attained to? And my contention is that if you trace it back, it was the people of the East who brought them out of the Dark Ages, who brought about the period, or ushered in or initiated the atmosphere that brought into Europe the period known as the Renaissance or the-- WARREN: --yes-- MALCOLM X:--reawakening of Europe. And, and this reawakening actually involved an era during which the people of Europe, who were coming out of the Dark Ages, were then adopting the value system of the people in the East, in the, of the oriental society. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: Many of which they were exposed to for the first time during the Crusades. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: Well, these were African ; these were African-Arab-Asian values. The only section of Europe that had a high value system during the Dark Ages was the, were those on the Iberian Peninsula in the Spanish-Portuguese area, southern France. And, and that high state of a culture existed there because of Africans known as Moors had come there and brought it there. So that value system has been handed right down in European society. And today when you find negroes, if they even look like they' ; re adopting these so-called middle-class values, standards, it' ; s not that they are taking something from the white man, but they are probably identifying again with the level or standard that these same whites have gotten from them back during that period. WARREN: You would approach Essien Udom' ; s theory on that ground, undercutting it? MALCOLM X: Undercutting it, definitely. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: I think that if he had something he didn' ; t take it back far enough in history-- WARREN:--I see-- MALCOLM X:--to get at the proper understanding of it. WARREN: You know, there' ; s a theory that' ; s sometimes enunciated by people like Reverend Wyatt Walker, for one, or Whitney Young, that the Black Muslim is primarily created by the white press. He exists but in a, in a, his importance was created by the white press. MALCOLM X: Wyatt doesn' ; t say that as much as Whitney Young does. WARREN: Both of them say it ; both of them said it to me, anyway. MALCOLM X: Well. WARREN: " ; A paper tiger" ; is what Wyatt, what Wyatt Walker calls it. MALCOLM X: Yeah. Well, I can answer them like this. Wyatt Walker can walk through Harlem. No one would know him. WARREN: Yeah. MALCOLM X: Whitney Young could walk through Harlem. No one would know him. Any of the Black Muslims can walk through Harlem and there' ; s people know them. I don' ; t think that anyone has been really created more by the white press than the civil right leaders. The white press itself created them. And they themselves in their pronouncements will tell you they need white allies, they need white help, they need white this. WARREN: Yes, some of them do. MALCOLM X: They are more a creation of the white press and the white community and are more dependent on the white community than any other group in the, in the community. WARREN: Almost word for word what you have said I could turn around as Wyatt Walker said to me about, not you personally, but about the whole Black Muslim movement. That if you go outside of New York City, Dr. King is known to 90 percent of the negroes in the United States and is respected and, and is identified more or less with him, at least as a--as a hero of one kind or another. That the Black Muslim, outside of one or two communities like New York, are unknown. MALCOLM X: Well, if that' ; s their opinion, that' ; s their opinion. I, I myself have never been concerned with whether we are considered known or unknown. It' ; s, it' ; s no problem of mine. WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: I will say this: that anytime there' ; s a fire in a negro community and it' ; s burning out of control, you send any one of them, send Whitney Young in to put it out. (laughs) WARREN: What do you think of Abraham Lincoln? MALCOLM X: I think that he probably did more to trick negroes than any other man in history. WARREN: Can you explain that? MALCOLM X: Because if he, if the, if he, well, there' ; s his own where he- -I have read where he said he wasn' ; t interested in freeing the slaves. WARREN: He said that, yes. MALCOLM X: So, he was interested in, in saving the Union. Well, most negroes have been tricked into thinking that Lincoln was a negro lover whose primary aim was to free them, and he died because he freed them. I think Lincoln did more to deceive negroes and to make the race problem in this country worse than any man in history. WARREN: How does Kennedy relate to-- MALCOLM X:--Kennedy, I relate right along with--with Lincoln. Lincoln, to me, Kennedy was a deceitful man. He was a cold-blooded politician whose purpose was to get elected. And the only time Kennedy made any, took any action to even look like he identified with negroes was when he was forced to. Kennedy didn' ; t even make his speech based on this problem being a moral issue until negroes exploded in Birmingham. During, during-- WARREN:--yes, that was (??) Birmingham. MALCOLM X: Right. During the whole month that negroes were being beaten by police and washed down the sewer with water hoses, Kennedy and--and King was in jail begging for the federal government to intervene, Kennedy' ; s reply was, " ; No federal statutes have been violated." ; And it was only when the negroes erupted that Kennedy come on the television with all his old pretty words. No, the man was a deceiver. He was deceitful and I will, I will never bite my tongue in saying that. I don' ; t think he was anything but a politician, and he used negroes to get elected and to get votes. WARREN: What about Roosevelt? MALCOLM X: Same thing. There was no--no president ever had more power than Roosevelt. Roosevelt could have solved many problems, and all he did was put, took negroes off welfare or, first he put them onto welfare, WPA and other projects that he had, and then, if it hadn' ; t been for Hitler going on the rampage, negroes would still be on the welfare. WARREN: What about Eleanor Roosevelt? MALCOLM X: Same thing. Eleanor Roosevelt was the chairman of the United Nations Human Rights Commission--I think it was--at a time when this country, and, and at the time that the Human Rights, the Covenant on Human Rights was formed, this country didn' ; t even sign it. This country has never signed the United Nations Covenant on Human Rights. They signed the Declaration of Human Rights. But if they had signed the covenant they would have to get it ratified by the Congress and the Senate, and they could never get the Congress and the Senate to--to agree to an international law on human rights when they couldn' ; t even-- (laughs)--get Congress or the Senate to, to agree on a civil rights law. So, Eleanor Roosevelt could easily have told negroes the deceitful maneuvering of the United States government that was going on behind the scenes. She never did it. In my opinion she was just another white woman who, whose profession was to make it appear that she was on the negro' ; s side. You have a lot of whites who are in this category. Therefore, they, they have made negro loving a profession. They are what I call professional liberals who take advantage of the confidence that negroes place in them and, therefore, this enhances their own prestige and it gives them key roles to play in the, in the politics of this country. WARREN: What about James Baldwin? MALCOLM X: Jimmy Baldwin-- WARREN:--yeah-- MALCOLM X:--is a negro writer. WARREN: What' ; s the content of that? MALCOLM X: He' ; s a negro writer who has gained fame because of his indictment and his very acid, acid description--I call it an acids description--of what' ; s going on in this country. My only, I don' ; t agree with his nonviolent, peaceful, loving approach. I, I just saw his play, Blues for Mr. Charlie, which I thought was an excellent play until it ended. And if you' ; ve seen the end of it, you' ; ll see what I mean. WARREN: I haven' ; t seen it yet. MALCOLM X: Well, you see it. All during the play I' ; m thinking that it has that when, at the final act that revenge will be taken, or justice will be given for the murder that has taken place. WARREN: I understand that the Ford Foundation is financing the play now- -I hear this ; I' ; m not certain of it--is financing it to keep it open a little while longer. Well, that' ; s a strange situation, isn' ; t it? MALCOLM X: Not to me. WARREN: Why? MALCOLM X: (laughs) I don' ; t know, but it' ; s not strange. I like, as I say, I like the play, Blues for Mr. Charlie, but the ending of it has the negro again forgetting that a lynching has just taken place. WARREN: That' ; s why the Ford Foundation might subsidize it, is that it? MALCOLM X: Well, I think that a white, that segments like that of the white power structure, will subsidize anything that implies that negroes should be forgiving and long-suffering. WARREN: You know Ralph Ellison' ; s work? MALCOLM X: Not too well. All I know is that he wrote The Invisible Man. WARREN: Yes, have you read that? MALCOLM X: No, but I know that, I got the point. WARREN: Yeah. What do you think of his position? MALCOLM X: I don' ; t know what his position is. If his position is that the negro in this society is an invisible man, then that' ; s a good position. Whatever else goes with it, I don' ; t know. WARREN: All right. Taking another, somewhat different tack, what about Nehru? MALCOLM X: I would like to add to-- WARREN:--please do-- MALCOLM X:--to Ellison' ; s Invisible Man. WARREN: Please. MALCOLM X: See, the negro as an invisible man, usually when a man is invisible he knows more about those who are visible and those who are visible know about him. And my contention is that the negro knows more about the white man and white society than the white man knows about the negro and negro society. WARREN: I think that' ; s true. MALCOLM X: The servant always knows his master better than the master knows his servant. The servant, the mas--the servant watches the master sleep, but the master never sees the servant sleep. The servant sees the master angry. The master never sees the servant angry. So the servant always knows the master better than the master knows the servant. In fact, the servant knows the house better than the master does. And my contention is that the negro knows this country better than the white man does, every facet of it, and when he wakes up he' ; ll prove it. Now, about Nehru? WARREN: Yes. MALCOLM X: I think that Nehru probably was a good man, although I didn' ; t go for it. I don' ; t go for anybody who is passive. I don' ; t go for anybody who is, who is, who advocates passivism or peaceful suffering in any form whatsoever. I don' ; t go for it. WARREN: What about Jesus Christ? MALCOLM X: I go for Mao Tse-tung much more than, than Nehru because I think that Nehru brought his country up in a beggar' ; s role. Their roles, the role of India and its reliance upon the West. [Tape 2, side 1 ends ; side 2 begins.] MALCOLM X: During the years since it got its supposed independence, has, has it today just as helpless and dependent as it was when it first got its independence, whereas in China, the Chinese fought for their independence. They became militant right from the out start, and today they' ; re, even though they aren' ; t loved, they are, they are respected. Though the West doesn' ; t love them, the, the West respects them. Now, the West doesn' ; t respect India, but it loves India. WARREN: I see your distinction. MALCOLM X: Can you see my distinction? WARREN: I do, indeed. MALCOLM X: I--I admire the, the stand of China and the stand of Mao Tse- tung, but I can' ; t admire with respect the stand of, of Nehru in India. I just can' ; t do it. WARREN: What about Reverend Galamison? MALCOLM X: Reverend Galamison is fighting a hard battle against great opposition, and I admire a man who fights a hard battle against great opposition. WARREN: No matter what' ; s he fighting for or against? MALCOLM X: Well, I admire a man who fights a battle against opposition, and if there wasn' ; t something about Galamison that the people, I notice that the power structure is against Galamison. And most of the negro leaders who get the support of the power structure end up being against Galamison. So my, my suspicious nature is that there' ; s something that Galamison, about Galamison that must have some good in it or some right in it. WARREN: Well, his policy is one of integration, and that isn' ; t exactly your policy. MALCOLM X: No, but at the same time his policy is intelligent enough where he can' ; t be used to attack me. And, and most of these other negro leaders who are supposedly integrationists aren' ; t that intelligent. WARREN: I see. MALCOLM X: (laughs) All right. WARREN: Are you being dragged away? MALCOLM X: Yes, I' ; m being-- WARREN:--all right. Well, I' ; ll pack up and-- [Tape 2 ends.] [End of interview.] All rights to the interviews, including but not restricted to legal title, copyrights and literary property rights, have been transferred to the University of Kentucky Libraries. audio Interviews may only be reproduced with permission from Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, Special Collections and Digital Programs, University of Kentucky Libraries. 0 http://www.nunncenter.net/ohms/render.php?cachefile=2002oh110_rpwcr005_malcomx_ohm.xml 2002oh110_rpwcr005_malcomx_ohm.xml https://www.kentuckyoralhistory.org/catalog/xt7m901zgp82

Sort Priority

0027

Interview Usage

Interviews may be reproduced with permission from Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, Special Collections, University of Kentucky Libraries.

Files

Citation

“Malcolm X,” The Robert Penn Warren Oral History Archive, accessed May 19, 2024, https://www.nunncenter.net/robertpennwarren/items/show/101.